History of the Bo’ness Fair

The morn’s the Fair and I’’ll be there, and I’ll hae up ma curly hair. I’ll meet ma lad at the fit o’ the stair, an’ I’ll gie him dram and a wee bit mair.

Monday 15th June 2020.

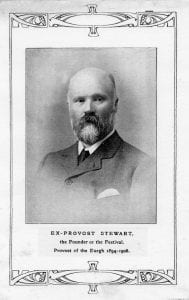

It was in 1897 that the Bo’ness Midsummer Children’s Festival as we know it today was instituted. The object being to introduce a pageant to replace the miners’ procession, which had been held annually for over a century. For some time, public interest in the miners’ festivals had been waning, and the Fair was gradually becoming regarded more particularly as a holiday time for the children. The reorganisation of the Fair in 1897 was prompted mainly by desire to give the children a more direct interest in the proceedings and at the same time to mark the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria in a manner fitting the occasion.

A model of the event was found in the Lanimer Day celebrations at Lanark, where the school children annually, and with great ceremony, elected a Queen from among themselves.

Miners

There was a tradition that originally, the Fair was devised and celebrated by the tenants’ and masters of the Duke of Hamilton and that the miners of the district only adopted the festival at a later period. Whether this be correct or not, the Fair had for many years’ past been almost entirely in the hands of the miners, who formed a class by themselves and held aloof the rest of the community. The reason for this attitude must be sought in the early history of the mining industry. It is recorded that the first coal to be mined in Scotland was at Carriden in the 13th Century. The miners in those days were bondsmen.

They were not at liberty to select their employment, nor could they work at another place without the permission of their superiors.

Until the latter part of the 18th century, it was customary for all Scottish miners to be thirled, that is, bound to the pits, as were any children who were born to them while they worked in them. Thus the bondage was continued from generation to generation and if any of the miners tried to escape from virtual slavery the colliery masters had the power to send their overseers to drag them back and to punish them severely. Even when a colliery owner sold his pit, the miners were included as part of the transaction. At last, 1774, a law was passed forbidding the thirling of miners and their families to the coal pits, but those already tied to the mines were not granted their freedom straightaway and it was not until 1779 that an Act declared that, “all the colliers in that part of Great Britain called Scotland, are hereby declared to be free from their seritude.”

Enter the Commissioners

As the century moved on, however, the feeling seems to have grown from that this annual festival was losing its significance. It was to celebrate this new-found liberty that the miners of Bo’ness who formed a very close-knit community of their own, staged their first Fair. From then on the Fair was held every year on the Friday in July which fell between the 12th and 19th, [the first Friday after the second Tuesday] a date already connected with one of the four feeing fairs for which Anne, Duchess of Hamilton gained Parliamentary permission shortly after she won her battle for burgh status for Bo’ness in 1668.

In1884 an invitation was issued by the Newtown Fair Committee and similar from the miners of Grangepans and Corbiehall to the Town Council and Police Commissioners to meet. Provost Ballantine after meeting the representatives from the three mining communities conveyed to the Commissioners an assurance that the miners would willingly fall in with any arrangements which the local authority might make for the festival. The Commissioners had many misgivings, fears were expressed lest they should be expected to get “fou like the rest” also what would they were for such an occasion. Most of them agreed with the Provost view that.

“at least for one day a year they should be on the same level as their neighbours” To forget any differences for a few hours to join in general friendship.

Provost rides in the procession

On the 13th of July1894 the Provost, Magistrates, Commissioners and local officials rode for the first time in the Fair Procession, in carriages which were placed immediately behind the Deacon of the Corbiehall miners. A bannerette – bearing the Burgh Coat of Arms and motto was proudly displayed. The leading carriages had scarlet -coated outriders. Two mounted policemen accompanied the carriage which carried the Provost and the Magistrates. It was recorded that “many were the respectful salutations the occupants received during the course of the march”

At Kinneil House, the civic dignitaries were received by the Duke ‘s estate factor Mr J.F. Macaulay, who provided them all with glasses of whisky toddy.

After a speech from the Provost the procession got underway again. Proceeding along the Coach road to Richmond, south past Newtown along Borrowstoun to Kinglass. Through Bonhard and Muirhouses to Carriden.

The Grange

There at the Grange the marchers refreshed themselves and joined in the sports and dancing to the pipes in Kinacres field. Mr Cadell entertained the Commissioners to lunch in the Grange. Also, Mr Cadell, himself, always welcomed his men and on this one day in the year, it is reported that the “Maister” relaxed his usually severe manner and even handed round the whisky toddy to his miners, an act which greatly delighted them.

Kinneil Band 1858

A brass band, imported during the early years from Falkirk, always accompanied the marchers and while they enjoyed their free drinks, they played on the lawn in front of the old Grange, before leading the procession down to the banks of the Forth, where horse races were held on the foreshore, throughout the afternoon.

Bo’ness Town Centre

The Vennel

Robert Burns

The most distinguished visitor to the Bo’ness races was Robert Burns, but he was little impressed with the standard of the races as he was with the rest of Bo’ness, which he described as, “that dirty ugly place, Borrowstounness”, and which certainly did not inspire him to verse. It is little wonder that Burns was not thrilled by the races, for the mounts were just local carriage and wagon horses, pressed into service for the day and generally most of them had already done duty earlier in the day, carrying the Deacon and other miners’ leaders at the head of the procession.

Once the last race was over the crowd returned to Corbiehall, where the booths and side stalls of the fairground were set up and the gingerbread sellers did a roaring trade. Later there was dancing in the Town Hall, where all miners and their wives and daughters could afford to join in the merrymaking, as they paid separately for each dance at one penny a time.

Drinking, was however, the main attraction of the Fair and the town’s many pubs and inns were crowded. In those days there were no licensing laws and the pubs stayed open throughout the night so that the festivities continued right into the following Saturday, or at least as long as the miners’ money lasted. The remainder of the weekend the miners spent sobering up, returning to the pits to start work again early on the Monday morning. Their annual holiday was over and there was only the next year to look forward to, to brighten their dreary existence, so they immediately appointed a new Deacon to act as their leader and make a start to the arrangements for the following year’s Fair.

A Fair Deacon

Read more tomorrow about the history of the Bo’ness Fair and see a photo of the very first Fair Queen